VI.

Entangled

Ecologies: Mapping Invasive Mussels in the Capitalocene

Noam Levinsky

Iovanni Romarion

Samuel Schuur

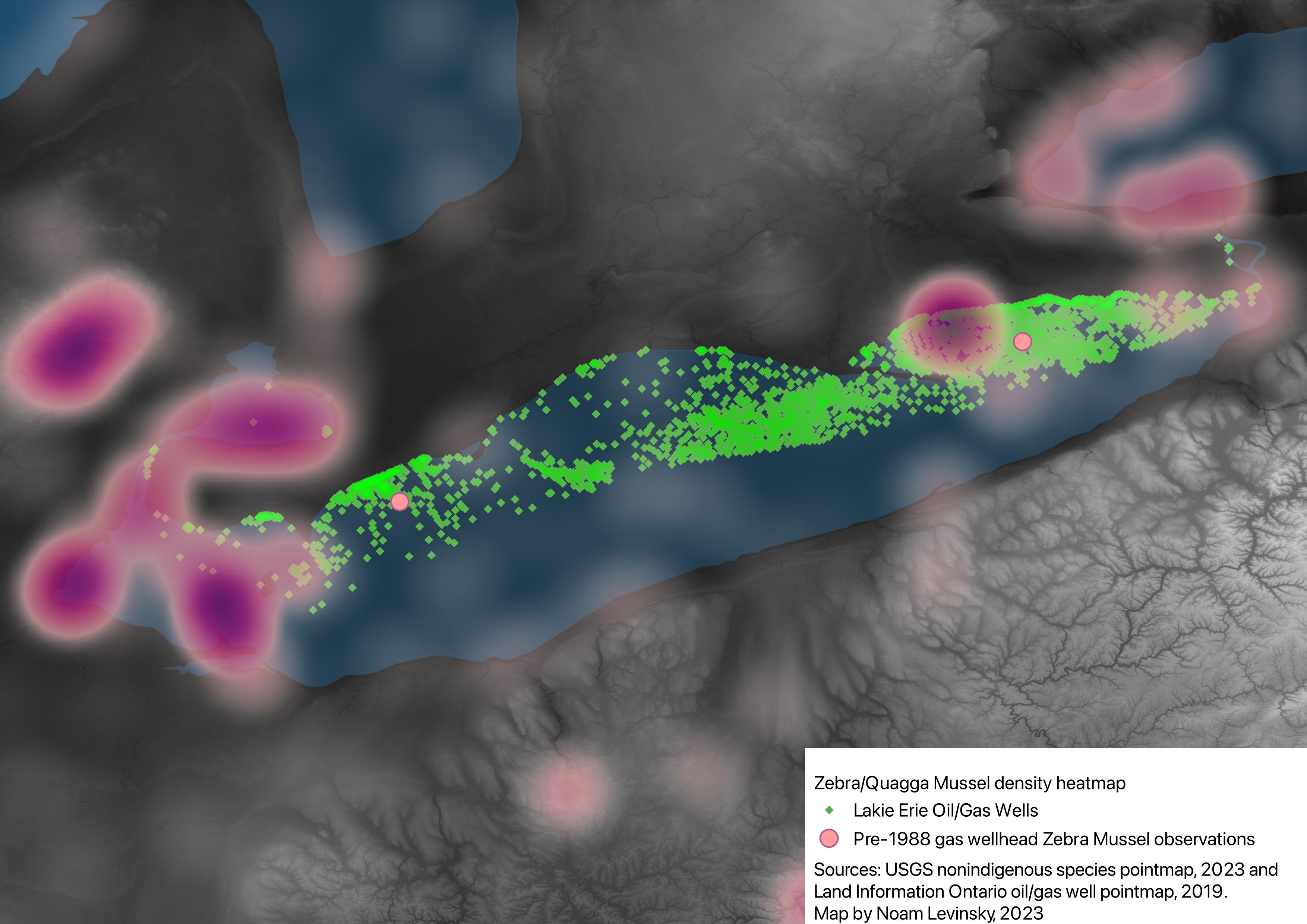

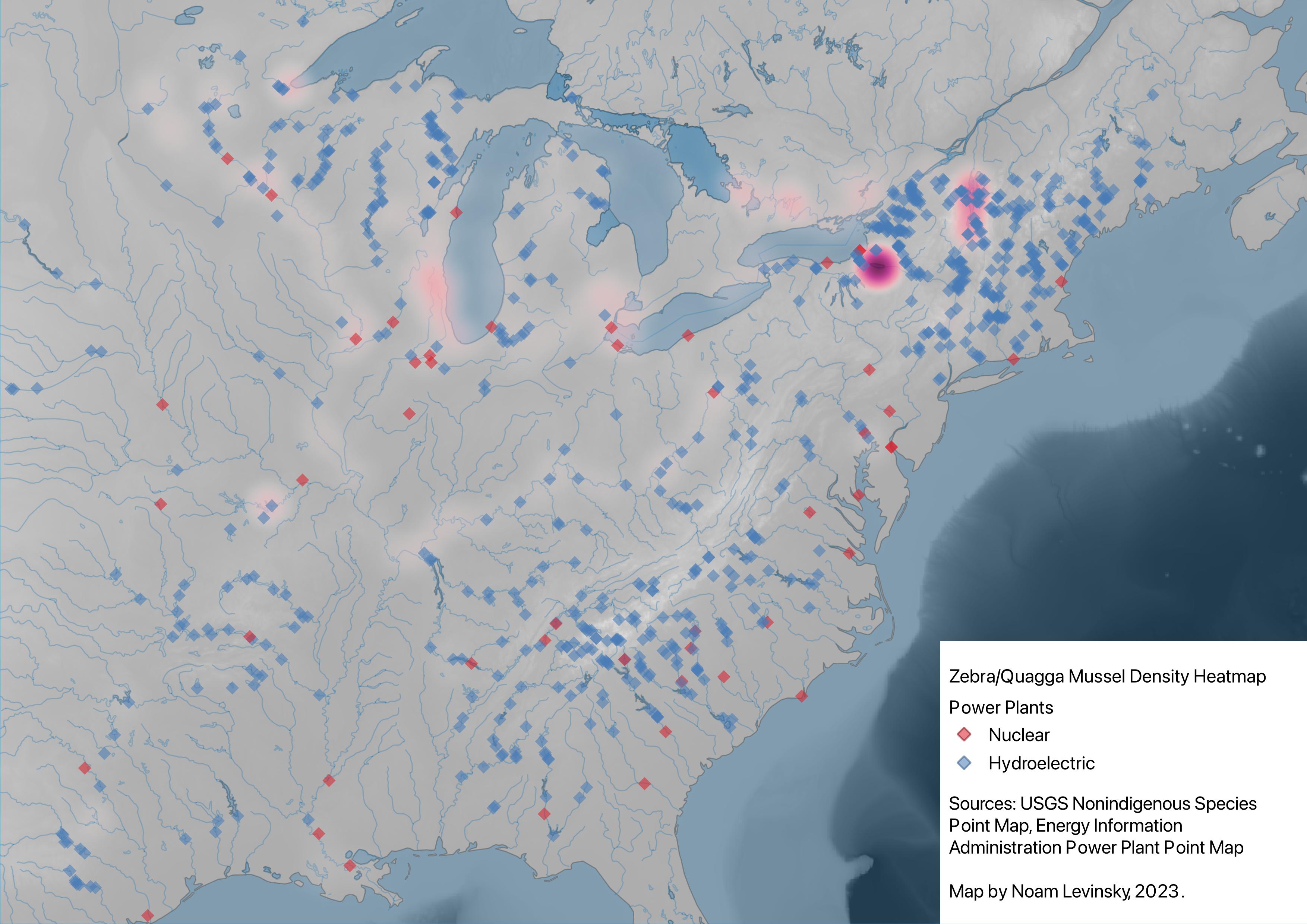

Dreissena polymorpha, colloquially known as the Zebra Mussel, is a small mollusk native to the Caspian and Black Seas (Koch 2021). But despite their size, Zebra Mussels and their relatives Quagga Mussels have become major ecological actors. Zebra mussels were first found in North America in 1986—decades after the St. Lawrence Seaway was built as a connection between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean navigable for large cargo ships (Carlton 2008). Yet, at some point, one or more ships passing through the Seaway released Zebra Mussels from their ballast tanks, extending the Mollusk’s range to a second continent. Above, you can see the spread of Zebra and Quagga Mussels since 1985 as it relates to the political-ecological process of Seaway traffic.

The ecological crisis of invasive mussels did not create itself. Rather, it was the result of a specific political-ecological configuration. The Seaway did not have to be built. The ¾ Coast did not have to be ecologically linked with the Black Sea. Yet, the forces of capitalism viewed the Great Lakes as frontiers that could be exploited for profit.

Indeed, Capitalism always pursues frontiers because “They offer places where the new cheap things can be seized—and the cheap work of humans and other natures can be coerced” (Moore and Patel, 2018). Through this opening of Great Lake ecologies to the never-ending quest for new commodities and markets, an ecological crisis was produced.

Invasive mussels have had profound effects not only on Great Lakes ecologies, but also on global economies. The frontier-pursuing drive of capitalism attempted to infrastructuralize the ¾ Coast into a thoroughfare for commerce, but invasive mussels struck back. The authors of the Feral Atlas agree, writing about the Great Lakes region: “In many times and places, including the hinterlands of Chicago, capital has imposed uniformity and simplification on ecological assemblages. Yet such infrastructural work always has feral effects, with unpredictable results for particular capitalists” (Tsing et al., 2021). This project seeks to map invasive mussels not merely as ecological forces of destruction, but as feralities, unpredictable externalities that strike back.

The first known observation of a Zebra Mussel was in 1986, when a Canadian oil executive noticed them on a buoy marking an offshore natural gas well in Lake Erie. By 1990, that same oil executive noted that his buoys were covered in so many mussels that they were sinking underwater from the weight, as well as that the oil wells themselves were being clogged by mussels (Carlton 2008). Zebra Mussels had gone from a novel alien species to a major economic threat.

The effects of Zebra and Quagga Mussels on the energy market aren’t limited to natural gas wells: water intake systems at hydroelectric and nuclear power plants are also vulnerable to mussel invasion. While it's possible to clear water intake pipes, the cost of keeping them mussel-free costs midwestern power plants up to three billion dollars annually (OPB Staff 2018). From Canadian offshore gas wells to American hydroelectric and nuclear plants to the many homes and businesses reliant on them for power, the mussel externality had gone feral.

The second discovery of Zebra mussels in North America was made in 1987, when they were found on the filters of a water filtration plant in Kingsville, Ontario (Carlton 2008). This incident set the stage for the subsequent alarm in the early 1990s, as Chicago's officials observed the impact of these mussels on various water intakes within the Great Lakes. The city, along with much of Cook County, depended on Lake Michigan for its water supply. This water was sourced through "water cribs" — substantial brick structures located two to three miles offshore, constructed between 1891 and 1935, to draw cleaner water, distanced from the city's pollutants. Fears escalated over the possibility of Zebra mussels clogging Chicago's water supply. In 1992, a report forecasted this calamity within three years. Consequently, the city opted to integrate permanent pre-chlorination pipes into the aged water mains to thwart any potential invasion by these mussels. However, a series of comical errors by contractors significantly delayed this process. During an attempt to drain a water supply tunnel leading to the Harrison Dever crib for pipe installation, a catastrophic collapse occurred, severing this water source. This led to concerns that the now-drained tunnel, situated beneath Lakeshore Drive, might cause sections of the highway to collapse. To mitigate this risk, two lanes of Lakeshore were closed for tunnel reinforcement with concrete, resulting in substantial traffic congestion (Illinois DOT, 2023). The attached map illustrates the water cribs and the collapse site, marked in red, alongside a traffic density overlay, depicted as cars per lane (Chicago City Council, 1911; Illinois DOT).

Ironically, while the Zebra mussel threat triggered some economic repercussions in traffic disruptions, and caused the loss of one of Chicago's water supplies, the mussels never materialized as a significant problem as initially feared. Moreover, as filter feeders, they inadvertently aided Chicago's filtration plants, improving Lake Michigan's water clarity over time, as depicted in the accompanying graph (Gitelman & Cheng, 2022). This unforeseen twist highlights the mussels' paradoxical role in both disrupting and inadvertently benefiting the city's water system.

The third known observation of zebra mussels was in December 1987, on the hull of a fishing tug boat docked in Kingsville, Ontario. The owner of the boat, Gerry Penner, also noted one year later that after another dry docking in the Kingsville port, the number of mussels on the hull of the boat went from four, to a complete covering of the hull, saying “You couldn’t put the point of a sharpened pencil anywhere on the boat and find a clear space” (Carlton 2008). This observation serves as a testament to the pervasiveness of zebra mussels in the lives of local residents, especially those who rely on the Great Lakes as a source of income.

The zebra mussel epidemic in the Great Lakes has devastated the lake’s ecology and the aquatic economy relying on it. For instance, zebra mussels have severely impacted the commercial fishing economy of the Great Lakes. The whitefish population, one of the pillars of local commercial fisheries, has declined sharply since the introduction of zebra mussels. The tribal fishers in Lake Huron reported they have “caught only 125,000 pounds of whitefish in 2020, a precipitous drop from over 2 million pounds in years prior” (Gitelman & Cheng 2022). This drastic reduction threatens the local communities who have relied on the Great Lakes for sustenance. As the zebra mussel continues to alter and damage the Great Lakes, the ramifications of the Capitalocene (where zebra mussels were brought to the Great Lakes through foreign shipping boats) become increasingly visible.

Aside from fishing economies, the zebra mussels epidemic has severely affected local tourism within Great Lakes communities. One of the consequences of the zebra mussel’s invasion was the proliferation of blue-green algae blooms in lakes. While the mussels filter almost all nutrients in the body of water they are in, they are ineffective against harmful algae blooms like Microcystis (Lorditch 2021). As a result, these algae blooms can thrive, causing harm to the animals and people that interact with the lakes they are in. For example, in Celina, Ohio, the local lake Grand Lake St. Marys has experienced “small businesses [closing down] or witnessing substantial reduction in revenues in the area of $35 to $45 million [and] Park revenue is down approximately $250,000 (Davenport & Drake 2011). This grim reality highlights the far-reaching consequences of the Capitalocene, as communities connected to the Great Lakes are grappling with collateral damage inflicted by capitalistic greed. As a result of the zebra mussel invasion, there is an urgent need for financial investment and comprehensive strategies to deal with this seemingly insurmountable and exponentially growing issue.

What began as a local ecological crisis in Lake Erie has rapidly become a threat not only to the ¾ Coast, but also to the world economy. Invasive mussels shut down fisheries and depress tourism economies. They clog and obscure the natural gas wells that fuel the accumulation of capital. Water intake pipes are blocked, exposing the vulnerability of power plants and urban drinking water systems. When Chicago tries to respond to invasive mussels, things only get worse: pipes are shut down and roads are closed. Multinational corporations lose money as their executives are stuck on Lake Shore Drive. For now, Zebra and Quagga Mussels are confined to their native European range as well as North America. But that may change soon, as climate change could make the Southern end of the American continent more susceptible to Zebra Mussel invasion (Davenport & Drake 2011). The feral entity has not been sufficiently contained.

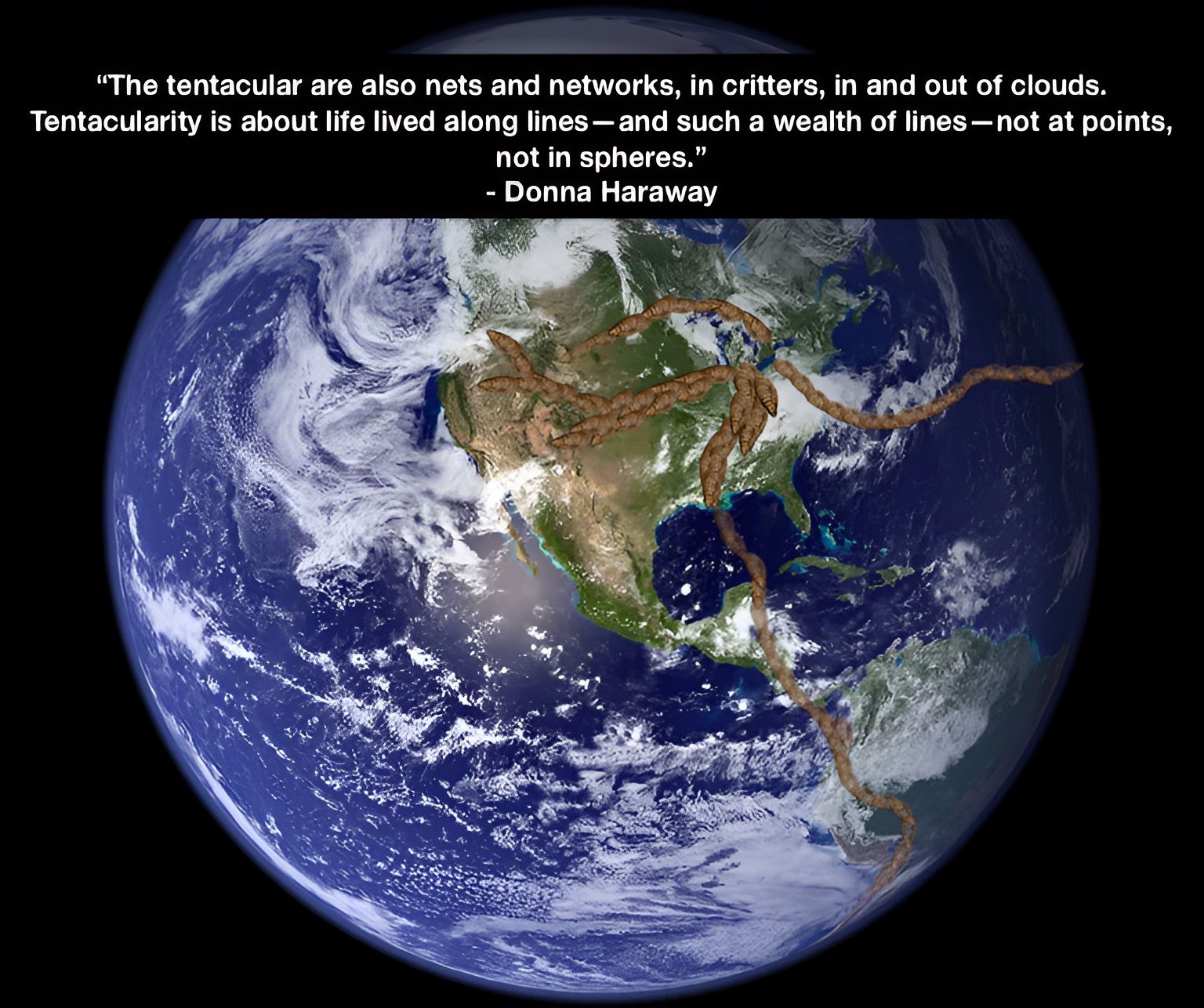

While the physical presence of Zebra and Quagga Mussels is felt only locally, their presence as feral externalities is felt globally. Transparent, ghostly, lines connect the ¾ Coast to markets and ecosystems across the planet. The Mussel, therefore, can be theorized as a tentacular entity (Haraway 2016)—a powerful entity that forms lines connecting and disrupting global political ecologies. The networks of global capitalism are powerful, but they are vulnerable to the feral tendrils of Zebra Mussels. Thus, the story of invasive mussels is not merely a story of crisis and loss at the hands of capitalism, but also a story of capitalism’s contingency when threatened by the more-than-human.

Bibliography

[1] Koch, Sophie. “Invasive Zebra Mussels.” National Parks Service, April 2, 2021. https://www.nps.gov/articles/zebra-mussels.htm.

[2] Carlton, James T. “The Zebra Mussel Dreissena polymorpha Found in North America in 1986 and 1987.” Journal of Great Lakes Research, Volume 34, Issue 4, 2008, Pages 770-773. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0380-1330(08)71617-4.

[3] Moore, Jason W, and Raj Patel. A history of the world in Seven cheap things: A guide to capitalism, nature, and the future of the planet. University of California Press, 2018.

[4] Tsing, Anna, et al. Feral Atlas. Stanford University Press, 2021.

[5] OPB Staff. “Faces of the Invasion: The Ripple Effect.” OPB, April 20, 2018. https://www.opb.org/news/series/silentinvasion/faces-of-the-invasion-the-ripple-effect/.

[6] "Exhibit D: Map of Sanitary District of Chicago." In Journal of the Proceedings of the City Council of the City of Chicago, Illinois, Regular Meeting, November 20, 1911. National Archives Catalog. Accessed December 7, 2023. [https://catalog.archives.gov/id/125849572?objectPage=2]

[7] Department of Sewers and Water (1954). Chicago Water System. Chicago: Department of Sewers and Water.

[8] Illinois Department of Transportation. "IRIS." Accessed December, 2023. [https://apps1.dot.illinois.gov/gist2/]

[9] Gitelman , Alec, and Allen Cheng. “Great Lakes Fish and Fisheries Suffer Stress of Warming Climate.” Detroit Free Press , July 1, 2022. https://www.freep.com/in-depth/news/local/michigan/2022/06/14/great-lakes-fish-fisheries-warming-climate/9925762002/.

[10] Lorditch, Emilie. “Are Zebra Mussels Eating or Helping Toxic Algae?” MSUToday, June 24, 2021. https://msutoday.msu.edu/news/2021/zebra-mussels-and-microcystis.

[11] Davenport, Tom, and Wendy Drake. “EPA Commentary - North American Lake Management Society (NALMS).” North American Lake Management Society, 2011. https://www.nalms.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/31-3-11.pdf.

[12] Petsch, D.K., Ribas, L.G., Mantovano, T. et al. “Invasive potential of golden and zebra mussels in present and future climatic scenarios in the new world.” Hydrobiologia 848, 2319–2330 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-020-04412-w

[13] Haraway, Donna. "Tentacular Thinking: Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Chthulucene," in, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene, Duke University Press, 2016.