I.

Localized Resistance to Plantation Logics

| Tatiana Jackson-Saitz | |

| Sofia Johansson | |

| Will Sampson | |

| Chloe Thompson |

Inherent in the Plantationocene is the existence of a “plantation logic” that gets reproduced as a constant way of abstracting the land and animals (McKittrick). This geostory tracks the plantation as a driver of climate change and violence flattening the freedoms and cultures of the Ojibwe people, from its racialized manifestations in the past, present, and in “plantation futures” (McKittrick).

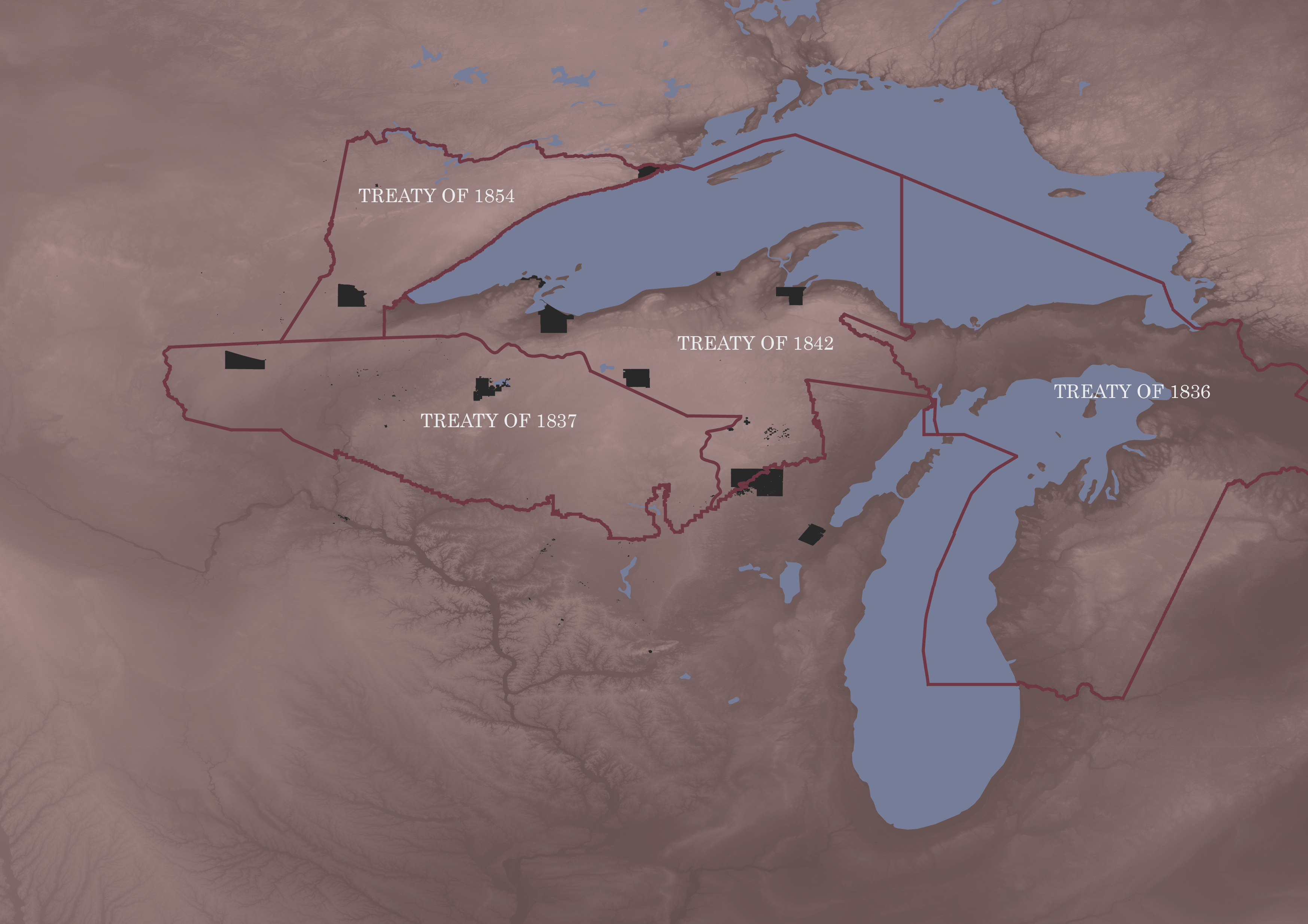

We begin at a fairly simple basemap of political boundaries and tracts with the express purpose of depicting the kind of violence that plantation logic can do in its oversimplification and monocultural understanding of land that creates hierarchies of territories. This basemap depicts the “lands of no one” (McKittrick). Within the Plantationocene, there are emancipatory possibilities at small, localized levels of change (Wolford). We will move between this basemap of plantation logic and callouts representing the richness of resistance through specific reservations, a resistance that is invisible at the large, imposed landscape of the plantation.

Act I: Lac Courte Oreille Band, Lake Superior Ojibwe (Wisconsin)

This first act of resistance we will examine is located in the Lac Courte Oreille Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe reservation—or more precisely, just off it. Shortly after the treaties in the mid-19th century that asserted Ojibwe rights to continue fishing and hunting off their reservations, these rights were ignored, and Ojibwe would be arrested for spearfishing in bodies of water off the reservation. The borders of the reservation depicted here cut through water, and in 1974, two brothers, Mike and Fred Tribble, chose to go slightly north (out of their reservation borders) to spearfish walleye in the part of Chief Lake/Lake Chippewa that technically belonged in Hunter, Wisconsin. They were arrested, and a court case in 1978 stated that when their reservation was established, they lost their rights to fish beyond that territory. The brothers continued appealing until 1983, when the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit ruled in favor of the Lac Courte Oreilles Band in a ruling now known as the Voigt Decision. This form of activism was taken up throughout the country as native tribes began to appeal to the courts and use them as a strategy for reasserting rights taken away from them by extractivist and colonialist decisions. The intentional triggering of these court cases through the Tribble arrests demonstrates a local level of resistance that works to re-assert past community ties to land in a logic beyond the extractive and imposing one of the plantation. It demonstrates the emancipatory possibility that lies in a small scale—contrasted against the political basemap which hides this landmark moment in history.

Act II: Red Cliff Band, Lake Superior Ojibwe (Wisconsin)

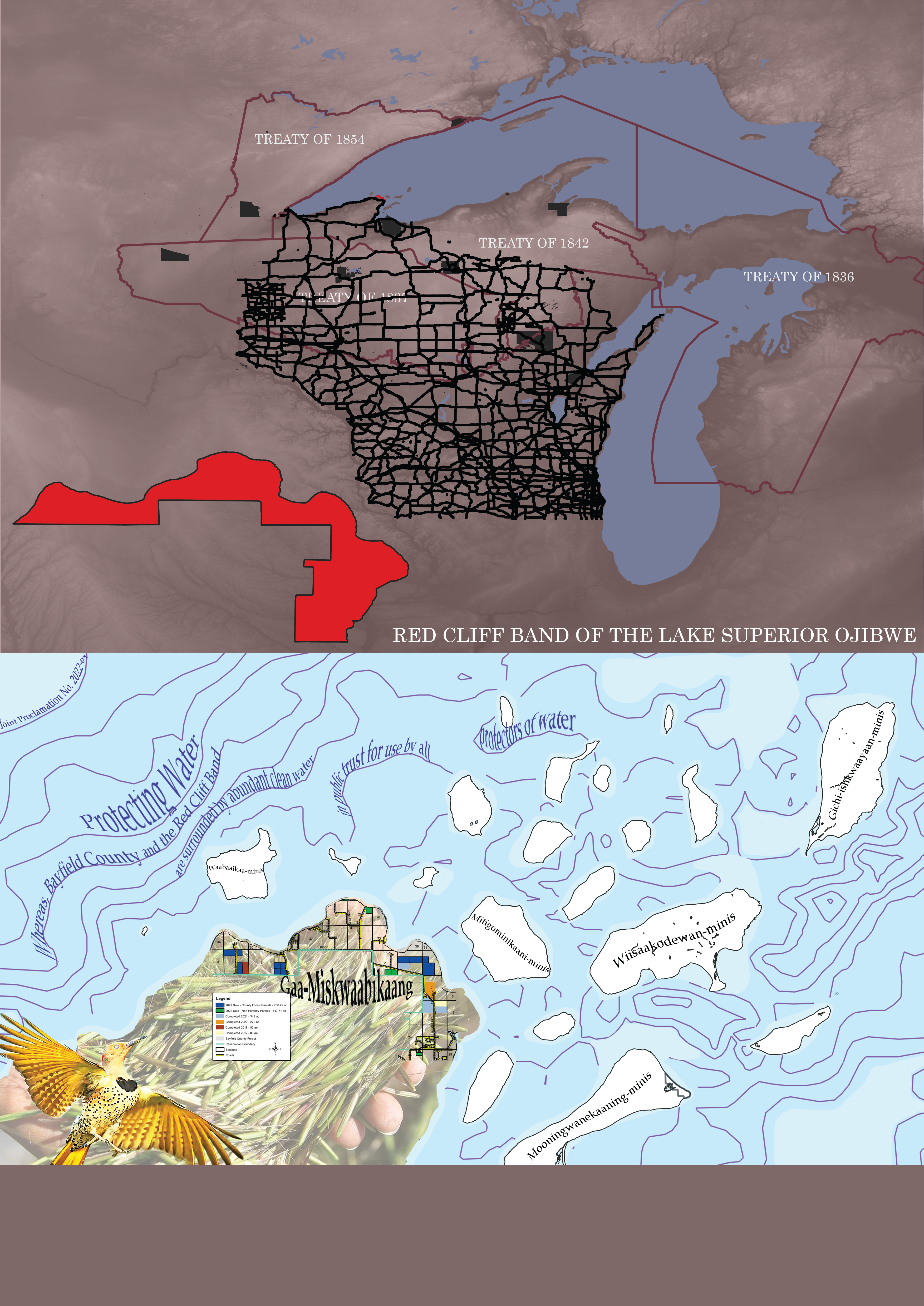

Our second act of resistance is located at the Red Cliff Band’s reservation in northern Wisconsin. The Red Cliff Band offers a profound example of resistance through land and water reclamation. The callout juxtaposes the base map of the federal highway system and state roads, which exemplify the Plantionocene due to their extreme extraction of land and resources and their expansion into Indigenous territories. They also represent capitalism through the transportation of extracted resources across the state, as well as the transportation of people for capitalist tourism. The callout asserts a resistance narrative by merging Ojibwe histories with the Red Cliff’s radical acts of the present. First, the history of the Red Cliff states that a sacred shell guided them on a generations-long journey moving west from the east coast, with seven stops to the “food that grows on water,” also known as manoomin. That seventh stop was Mooningwanakawning, the island to the east of the mainland Red Cliff reservation. Mooningwanakawning means place of the yellow flicker bird, and thus both manoomin and the yellow flicker bird have important historic and present cultural significance for the Red Cliff. They also represent resistant modes of conceptualizing place. These symbols are united with representations of the Red Cliff’s present acts of reclamation. Beyond the United States’ initial stealing of Ojibwe land, the State of Wisconsin took a significant amount of the Red Cliff’s land during the 20th century due to tax delinquency, which means they were unable to pay taxes on land within their own reservation to the government that took all their land to begin with. This is an incredibly violent case of the Plantionocene operating in the present, with a monetary value being placed on land and that value overruling the lives of the people living with that land. In 2000, the tribe initiated a Tribal Land Recovery Project to reclaim this land. Between 2017 and 2022, the realization of that reclamation occurred and the tribe got over 1,500 acres of land back. Part of their central reasoning in seeking to reclaim this land was the harm that disjointed ownership and management posed to habitat connectivity and climate resiliency efforts. They also emphasized the importance of being able to take care of the land in order to take care of the water. Though Gichigami (Lake Superior) was also stolen by the federal government, the Red Cliff has proposed various efforts to reclaim their connection to the lake and reestablish the responsibility all beings have for it and for each other. After the success of their land reclamation, they made a joint proclamation with Bayfield County titled “Protecting Water,” stating the role both parties have as “protectors of water.” These efforts, along with using the Ojibwemowin names for islands and places, are all important, tangible moves of resistance to both the geographical and political norms of the Plantationocene.

Act III: Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, L’Anse Reservation (Michigan)

Our third story of resistance involves the people of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Community (KBIC) who live on the L’Anse Reservation lands in Baraga County, Michigan. Throughout the 20th century, the area was home to facilities belonging to Ford Motors, Celotox, and now Certainteed, which is listed on the EPA’s Toxic Release Inventory. The longstanding impacts of these industrial processes are deeply intertwined with colonialism, resource extraction, and the Plantationocene as these companies engaged in logging and mining in the area resulting in impacts on the health of Indigenous communities. These activities also had severe impacts on the environmental health of the air, land, and water in the region. In particular, the water quality of the lakes and rivers within the KBIC greatly decreased as they were contaminated with dangerous pollutants which then flowed into Lake Superior. Despite the clear impacts that industrial activities were having on KBIC waters and beyond, the KBIC had no decision-making authority over the water quality standards and therefore no control over the distribution of federal permits for industrial activity in the area, which requires the corporations to adhere to water standards. This changed in 2020, when the KBIC submitted an application to the EPA for Treatment as A State for the authority to set water quality standards for the bodies of water within the reservation. The application was approved and the KBIC has been able to take one step towards reclaiming water sovereignty and repairing their relationship to the land which was eradicated by plantation economies. This is another example of the ways in which the Plantation persists in tangible ways in the present and continues to shape the environment of the future. The exploitation on and near KBIC land exposes the “artificial separation” between colonization and capitalism and highlights the ways in which core tenants of the plantation economy play a leading role in environmental degradation.

Act IV: “Pine Treaty,” Lac du Flambeau Reservation (Wisconsin)

Our fourth exploration of resistance comes from a more indirect perspective of plantation logic. Logging has been and will be a potentially extractive practice central to this narrative within the three ceded territories of interest. The Treaty of 1837 Land Cessation Treaty is often referred to as the “Pine Treaty” in reference to the valuable timber which was ceded to Westerners (National Archives Catalog, 1837). Prior to Western logging practices, the boreal forests of Northern Wisconsin were flourishing and when timber was harvested, indigenous populations did so in a sustainable manner. After the Treaty of 1837 was signed, massive, profit-driven mills were constructed to harvest the bounty of the forests in a uniquely capitalist fashion. Slow-growth, sustainable harvesting techniques formerly practiced by the Ojibwe were unable to compete with the veracity and swiftness of the Western logging industry. By the turn of the century, over 85% of logs in the forest had been cut and processed for human consumption (Steen-Adams, Langston, and Mladenoff, 2010). Since then, the forest cover has partially recovered from historial minimums, and Ojibwe peoples communities continue to sustainably harvest timber on their reservations and it remains a steadfast central practice today; however, a new force increasingly threatens their access to forests, regardless of how sustainable the harvesting techniques utilized: anthropogenic climate change (Hansen, 2015). Polluting, extractivist practices perpetuated by the Plantation lead to global land changes that know no boundary, and thus infiltrate geographies across the globe. On Ojibwe reservations today, global warming makes local climates unsuitable for forest survival, stripping the lands of their inherent productive capacity regardless of who or what “controls” the land. This example demonstrates the pervasiveness of the Plantation and questions how effective resistance can be when impacts of the Plantation are truly global phenomenons.

In the same time frame that George Catlin was painting Ojibwe spearfishing—an implicit or intentional recognition of pre-existing native traditions and practices—treaties were being signed to steal land from the Ojibwe. Despite these treaties claiming to protect these traditions and practices by allowing for off-reservation fishing, there were attempts over the course of the next century and more to intentionally and systematically dissolve those community practices. The “imposition of plantations around the world was (and is) predicated on the removal or absorption of preexisting community ties and reconfiguration around commodity production” (Wolford). Reconfiguring native conceptions of fishing when they didn’t serve American political and economic frameworks of fishing and preventing local practices from serving as community ties was an enactment of plantation logic on the Ojibwe. After the Voigt decision which returned to these treaty rights, honoring them and allowing for off-reservation fishing, protests broke out and continued until 1991 at boat landings with the aim of threatening and removing Ojibwe people who chose to exercise their rights and spearfish beyond reservation boundaries.

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission reported that the Ojibwe speared only 3% of the walleye in treaty-ceded territory, and Ojibwe tribes stock lakes with walleye as well—regeneratively taking care of the walleye rather than solely extracting them.

The map above seeks to exemplify the normative representations of the Plantationocene to contrast the Red Cliff callout of resistance at relatively the same scale. First, to contrast the Ojibwemowin names in the original callout, I used the official United States colonizer names for the islands and city on the mainland, Bayfield. Additionally, the Red Cliff reservation is depicted in black to represent the colonizer’s view of reservations as the “lands of no one” (McKittrick). Moreover, there is an outline of Highway 13 in Lake Superior, which traverses the mainland and the Red Cliff reservation, to mimic the bathymetry lines in the original callout. This demonstrates the Plantionocene’s emphasis on capitalist systems over ecological values. The mainland features a collage of Plantationocene extractive practices in the area, including the highway, logging, and industrial agriculture. Finally, there is a historic document featuring an advertisement for the sale of Indigenous land in Wisconsin, tying back to the original theme of stolen land.

The painting is a reconstruction of the natural world by Tom Uttech titled Mamakadendagwad, translated as "it is astonishing" from the Ojibwe language. Birds and animals travel in the painting from right to left, spurred by an unknown threat—the video then erases this world and gradually relegates it to treaty boundary definitions and then the Ojibwe reservations. We don’t know what the spatialized conceptions of land were before these treaty boundaries in the 19th century, so that first definition of Ojibwe land through colonialist logic is already a form of loss. Wolford writes that the plantation relies on “the prioritization of scale, segmentation, hierarchy, clearly defined boundaries, and an extractive relationship with the local community,” and as we move from the richness and complexity represented by Uttech’s painting in the astonishing natural world to disjointed, fragmented, defined boundaries, we see the violence and loss within the Plantationocene.

Bibliography

1_TitlePage&Basemap

Falck, Miles, Unglaube, Dara et al. Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), Ceded Territory Boundaries, January 2015, https://maps.glifwc.org/#on=glifwc_public_labels/labels_ceded_terr itories;glifwc_labels/labels_tribal_lands;glifwc_public_ceded/ceded_territories_polygons;glifwc_govt/tribal_lands_glifwc;glifwc_public_govt/counties_natatlas;openstreetmap/osm_mapnik&loc=2445.98490512564;-9762719.342570093;5700582.732404122, https://data.glifwc.org/ceded/downloads/Ceded.Territory.GIS.Version.2.1.pdf.

US Census Bureau, Geography Division, American Indian Area Geography, 2020 TIGER/Line® Shapefiles,https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2020&layergroup=American+Indian+Area+Geography.

Native Land Information System, “2019 BIA Recognized Tribal Land Ownership by Reservation, State, County,” Created May 15, 2020, Last Updated August 19, 2021, https://data.nativeland.info/dataset/ 2019-tribal-land-ownership-by-state

Earth Science Data Systems, NASA. “SRTM.” NASA, 2000. https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/sensors /srtm.

Natural Earth, Lakes + Reservoirs, https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-physical- vectors/10m-lakes/

2_Fishing&Treaty_Violations

Earth Science Data Systems, NASA. “SRTM.” NASA, 2000. https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/sensors /srtm.

Falck, Miles, Unglaube, Dara et al. Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), Ceded Territory Boundaries, January 2015, https://maps.glifwc.org/#on=glifwc_public_labels/labels_ceded_terr itories;glifwc_labels/labels_tribal_lands;glifwc_public_ceded/ceded_territories_polygons;glifwc_govt/tribal_lands_glifwc;glifwc_public_govt/counties_natatlas;openstreetmap/osm_mapnik&loc=2445.98490512564;-9762719.342570093;5700582.732404122, https://data.glifwc.org/ceded/downloads/Ceded.Territory.GIS.Version.2.1.pdf.

Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), River Segments Available for Open Water Spearing and Netting, February 2018, http://glifwc.org.

Native Land Information System, “2019 BIA Recognized Tribal Land Ownership by Reservation, State, County,” Created May 15, 2020, Last Updated August 19, 2021, https://data.nativeland.info/dataset/ 2019-tribal-land-ownership-by-state

Natural Earth, Lakes + Reservoirs, https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-physical- vectors/10m-lakes/

Special to The New,York Times. "Congress Expected to Uphold Treaties on Indians' Fishing: A Raging Controversy." New York Times (1923-), Jan 16, 1978. http://proxy.uchicago.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/congress-expected-uphold-treaties-on-indians/docview/123862747/se-2.

US Census Bureau, Geography Division, American Indian Area Geography, 2020 TIGER/Line® Shapefiles,https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2020&layergroup=American+Indian+Area+Geography.

US Census Bureau, Geography Division, American Indian Area Geography, 2020 TIGER/Line® Shapefiles,https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2020&layergroup=American+Indian+Area+Geography.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, “Walleye,” https://nas.er.usgs.gov/queries/FactSheet.aspx?speciesID=831

Vaisvilas, Frank. “Torches and birchbark canoe guide Ojibwe man as he revives ancient tribal spearfishing tradition in northern Wisconsin,” Green Bay Press-Gazette, May 17 2022, https://www.greenbaypressgazette.com/story/news/native-american-issues/2022/05/17/tribal-spearfishing-northern-wisconsin-ceded-territories-using-birchbark-canoe-torches/9746860002/.

WI DNR Data Curator, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, “24k Hydro Waterbodies (Open Water),” Published August 9, 2017 and Updated October 26, 2022, https://data-wi-dnr.opendata.arcgis.com/datasets/wi-dnr::24k-hydro-waterbodies-open-water/explore?filters=eyJXQVRFUkJPRFlfTkFNRSI6WyJDaGllZiBFZHdhcmRzIExha2UiXX0%3D&location=45.914198%2C-91.313101%2C12.81

3_Reclamation_of_Land&Water

Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights. “Rights of Manoomin.” Center for Democratic and Environmental Rights, 2022. https://www.centerforenvironmentalrights.org/rights-of-manoomin.

Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC). “GLIFWC Public Web Map Service.” Dataset - Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), July 6, 2023. https://glifwc.org/geodata/dataset/glifwc-public-wms.

Kunze, Jenna. “Chippewa Tribe Gets 1,500 Acres of Lake Superior Land Back in NW Wisconsin.” Native News Online, August 30, 2022. https://nativenewsonline.net/sovereignty/chippewa-tribe-gets-1-500-acres-of-lake-superior-land-back-in-nw-wisconsin.

Red Cliff. “Home.” Welcome to Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, 2023. https://www.redcliff-nsn.gov/.

Red Cliff. “Red Cliff Reclaims Land from Bayfield County, Both Parties Sign Proclamation to Protect Water Resources.” Welcome to Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, June 9, 2022. https://www.redcliff-nsn.gov/news_detail_T10_R84.php.

United States Census Bureau. “2020 Tiger/Line® Shapefiles: American Indian Area Geography.” United States Census Bureau, 2020. https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2020&layergroup=American%2BIndian%2BArea%2BGeography.

US Bureau of Indian Affairs. “2019 BIA Recognized Tribal Land Ownership by Reservation, State, County.” Native Lands Data Portal, August 19, 2021. https://data.nativeland.info/dataset/2019-tribal-land-ownership-by-state.

Wisconsin First Nations. “Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.” Wisconsin First Nations, February 28, 2023. https://wisconsinfirstnations.org/red-cliff-band-of-lake-superior-chippewa/.

4_Extraction&WaterQuality

Baraga County Historical Museum, “1930’s picture of the Ford Sawmill in L’Anse,” http://www.baragacountyhistoricalmuseum.com/photohistory/picture_ford_sawmill_1930s_2.JPG/.

Baraga County Historical Museum, “1881 detailed aerial drawing of the Village of L’Anse,” http://www.baragacountyhistoricalmuseum.com/photohistory/picture_lanse_1880s_drawing.JPG.

Baraga County Historical Museum, “1900's picture of an old stone quarry located just north of L’Anse,” http://www.baragacountyhistoricalmuseum.com/photohistory/picture_lanse_1900s_stone_quarry.jpg.

Blok, Andrew. “‘Our community is a fishing community:’ Michigan tribe seeks to set its own water standards.” Great Lakes Echo, 2019, https://greatlakesecho.org/2019/06/19/our-community-is-a-fishing-community-michigan-tribe-seeks-to-set-its-own-water-standards/.

Environmental Protection Agency, “EPA Toxic Release Inventory (TRI) Program,” 2023, https://www.epa.gov/toxics-release-inventory-tri-program/tri-basic-data-files-calendar-years-1987-present.

Natural Earth, Rivers + Lake Centerlines, https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-physical-vectors/10m-rivers-lake-centerlines/.

Natural Earth, Lakes + Reservoirs, https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-physical-vectors/10m-lakes/.

US Census Bureau, Geography Division, American Indian Area Geography, 2020 TIGER/Line® Shapefiles,https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2020&layergroup=American+Indian+Area+Geography.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, “Approval of the Keweenaw Bay Indian Commmunity’s Application for Treatment in a Similar Manner as a State for the Clean Water Act Sections 303(c) Water Quality Standards and 401 Certification Programs,” 2020, https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-02/documents/placeholder_0.pdf.

5_Forest_Loss

Earth Science Data Systems, NASA. “SRTM.” NASA, 2000. https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/sensors/srtm.

Falck, Miles, Unglaube, Dara et al. Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), Ceded Territory Boundaries, January 2015, https://maps.glifwc.org/#on=glifwc_public_labels/labels_ ceded_territories;glifwc_labels/labels_tribal_lands;glifwc_public_ceded/ceded_territories_polygons;glifwc_govt/tribal_lands_glifwc;glifwc_public_govt/counties_natatlas;openstreetmap/osm_mapnik&loc=2445.98490512564;-9762719.342570093;5700582.732404122, https://data.glifwc.org/ceded/downloads/Ceded.Territory.GIS.Version.2.1.pdf.

Hansen, M. C., P. V. Potapov, R. Moore, M. Hancher, S. A. Turubanova, A. Tyukavina, D. Thau, S. V. Stehman, S. J. Goetz, T. R. Loveland, A. Kommareddy, A. Egorov, L. Chini, C. O. Justice, and J. R. G. Townshend. 2013. High-Resolution Global Maps of 21st-Century Forest Cover Change. Science 342 (15 November): 850-53. Data available on-line from:https://glad.earthengine.app/view/global-forest-change.

US Census Bureau, Geography Division, American Indian Area Geography, 2020 TIGER/Line® Shapefiles, https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2020& layergroup=American+Indian+Area+Geography.

Native Land Information System, “2019 BIA Recognized Tribal Land Ownership by Reservation, State, County,” Created May 15, 2020, Last Updated August 19, 2021, https://data.nativ eland.info/dataset/2019-tribal-land-ownership-by-state

Natural Earth, Lakes + Reservoirs, https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-physical-vector s/10m-lakes/

Research/Journal Articles/Readings

Haraway, Donna, Noboru Ishikawa, Scott F. Gilbert, Kenneth Olwig, Anna L. Tsing, and Nils Bubandt. “Anthropologists Are Talking – About the Anthropocene.” Ethnos 81, no. 3 (May 26, 2016): 535–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2015.1105838.

Kaeding, Danielle. “Ojibwe tribes in Wisconsin celebrate 40th anniversary of landmark decision on treaty rights,” Wisconsin Public Radio, September 28, 2023, https://www.wpr.org/ojibwe-tribes-wisconsin-celebrate-40th-anniversary-landmark-decision-treaty-rights.

McKittrick, Katherine. “Plantation Futures.” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17, no. 3 (November 1, 2013): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1215/07990537-2378892.

Steen-Adams, M., Langston, N., & Mladenoff, D. (2010). Logging the Great Lakes Indian Reservations: The Case of the Bad River Band of Ojibwe. American Indian Culture and Research Journal , 34(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.17953

Wolford, Wendy. “The Plantationocene: A Lusotropical Contribution to the Theory.” Annals of the American Association of Geographers 0, no. 0 (February 11, 2021): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/24694452.2020.1850231. https://www.are.na/block/16331832.

Additional Drawings

6_Walleye_Wars

Catlin, George. Ojibwe Spearing Salmon by Torchlight, 1846-1848, oil on canvas, 19 1⁄2 x 27 1⁄2 in. (49.6 x 69.9 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.575, https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/ojibwe-spearing-salmon-torchlight-4297.

Johnson, Dirk. Special to The New York Times. "Indian Hunting Rights Ignite a Wisconsin Dispute: Tensions between Races Mar Everyday Relations, Even in Sports." New York Times (1923-), May 16, 1987. http://proxy.uchicago.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/indian-hunting-rights-ignite-wisconsin-dispute/docview/110767945/se-2.

Falck, Miles, Unglaube, Dara et al. Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), Ceded Territory Boundaries, January 2015, https://data.glifwc.org/ceded/downloads/Ceded.Territory.GIS.Version.2.1.pdf.

La Pointe of Lake Superior, Wisconsin Territory, October 4, 1842,” https://catalog.archives.gov/id/68161617?objectPage=7.

Lauren Ina Special to The Washington Post. "Wisconsin Fights Annual Fishing War: Chippewas Exercise Spearfishing Rights in Midst of Media Circus." The Washington Post (1974-), Apr 24, 1990. http://proxy.uchicago.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/wisconsin-fights-annual-fishing-war/docview/140204044/se-2.

National Archives Catalog, “Ratified Indian Treaty 242: Chippewa of the Mississippi and Lake Superior -

National Archives Catalog, “Ratified Indian Treaty 223: Chippewa - Wisconsin Territory, July 29, 1837,” https://catalog.archives.gov/id/68144559?objectPage=5.

National Archives Catalog, “Ratified Indian Treaty 269: Wisconsin, May 12, 1854,” https://catalog.archives.gov/id/81145645?objectPage=3.

7_Plantationocene_Exemplified_in_the_Red_Cliff_Area

Boxer, Andrew. “Native Americans and the Federal Government.” History Today, 2009. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/native-americans-and-federal-government.

NRDC. “Industrial Agriculture 101.” Be a Force for the Future, January 31, 2020. https://www.nrdc.org/stories/industrial-agriculture-101.

US Bureau of Indian Affairs. “2019 BIA Recognized Tribal Land Ownership by Reservation, State, County.” Native Lands Data Portal, August 19, 2021. https://data.nativeland.info/dataset/2019-tribal-land-ownership-by-state.

Walker, Mark. “Highways Have Sliced through City after City. Can the U.S. Undo the Damage?” The New York Times, May 25, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/05/25/us/politics/biden-removing-highways.html.

08_Land_Loss

Falck, Miles, Unglaube, Dara et al. Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), Ceded Territory Boundaries, January 2015, https://maps.glifwc.org/#on=glifwc_public_labels/labels_ceded_territories;glifwc_labels/labels_tribal_lands;glifwc_public_ceded/ceded_territories_polygons;glifwc_govt/tribal_lands_glifwc;glifwc_public_govt/counties_natatlas;openstreetmap/osm_mapnik&loc=2445.98490512564;-9762719.342570093;5700582.732404122, https://data.glifwc.org/ceded/downloads/Ceded.Territory.GIS.Version.2.1.pdf.

US Census Bureau, Geography Division, American Indian Area Geography, 2020 TIGER/Line® Shapefiles,https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2020&layergroup=American+Indian+Area+Geography.

Uttech, Tom, Mamakadendagwad, 2015-2016, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase made possible by the American Art Forum, 2017.3, © 2016, Tom Uttech, courtesy Alexandre Gallery, New York, https://edan.si.edu/saam/id/object/2017.3.

09_Timber_Juxtaposition

Falck, Miles, Unglaube, Dara et al. Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), Ceded Territory Boundaries, January 2015, https://maps.glifwc.org/#on=glifwc_public_labels/labels_ceded_terr itories;glifwc_labels/labels_tribal_lands;glifwc_public_ceded/ceded_territories_polygons;glifwc_govt/tribal_lands_glifwc;glifwc_public_govt/counties_natatlas;openstreetmap/osm_mapnik&loc=2445.98490512564;-9762719.342570093;5700582.732404122, https://data.glifwc.org/ceded/downloads/Ceded.Territory.GIS.Version.2.1.pdf.

US Census Bureau, Geography Division, American Indian Area Geography, 2020 TIGER/Line® Shapefiles,https://www.census.gov/cgi-bin/geo/shapefiles/index.php?year=2020&layergroup=American+Indian+Area+Geography.

Native Land Information System, “2019 BIA Recognized Tribal Land Ownership by Reservation, State, County,” Created May 15, 2020, Last Updated August 19, 2021, https://data.nativeland.info/dataset/ 2019-tribal-land-ownership-by-state

Earth Science Data Systems, NASA. “SRTM.” NASA, 2000. https://www.earthdata.nasa.gov/sensors /srtm.

Natural Earth, Lakes + Reservoirs, https://www.naturalearthdata.com/downloads/10m-physical- vectors/10m-lakes/

Dethulstrup, Thure, Artist. Logging in northern Wisconsin / drawn by T. de Thulstrup, Zimerman & Negri, se. Wisconsin, 1885. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/92501636/.

Detroit Publishing Co., Publisher. Mills from railroad bridge, Eau Claire, Wis. United States Eau Claire Wisconsin, None. [Between 1880 and 1899] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016799263/.

10_Polluted_Waters

Baraga County Historical Museum, “1940's picture of 2 ford lumber barges loading lumber at the Ford Sawmill in L’Anse,” http://www.baragacountyhistoricalmuseum.com/photohistory/picture_ford_sawmill_1940s_5.JP.

Eisenstaedt, Alfred. “Disturbing Photographs Show Pollution in the Great Lakes Before the Clean Water Act,” The LIFE Picture Collection, https://www.life.com/nature/photos-great-lakes-pollution/.

Falck, Miles, Unglaube, Dara et al. Great Lakes Indian Fish & Wildlife Commission (GLIFWC), Ceded Territory Boundaries, January 2015, https://maps.glifwc.org/#on=glifwc_public_labels/labels_ceded_terr itories;glifwc_labels/labels_tribal_lands;glifwc_public_ceded/ceded_territories_polygons;glifwc_govt/tribal_lands_glifwc;glifwc_public_govt/counties_natatlas;openstreetmap/osm_mapnik&loc=2445.98490512564;-9762719.342570093;5700582.732404122, https://data.glifwc.org/ceded/downloads/Ceded.Territory.GIS.Version.2.1.pdf.

Keweenaw Bay Indian Community, “Application for Programmatic Approval under Section 401/303 of the Clean Water Act,” 2020, https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2019-04/documents/application_for_programmatic_approval_under_section_401-303_of_the_clean_water_act.pdf.

Archival Media:

01_Land_For_Sale

Boxer, Andrew. “Native Americans and the Federal Government.” History Today, 2009. https://www.historytoday.com/archive/feature/native-americans-and-federal-government.

02_Joint_Proclamation_Protecting_Water

Red Cliff. “Red Cliff Reclaims Land from Bayfield County, Both Parties Sign Proclamation to Protect Water Resources.” Welcome to Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, June 9, 2022. https://www.redcliff-nsn.gov/news_detail_T10_R84.php.

03_Red_Cliff_Land_Repatriation

Red Cliff. “Red Cliff Reclaims Land from Bayfield County, Both Parties Sign Proclamation to Protect Water Resources.” Welcome to Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Chippewa, June 9, 2022. https://www.redcliff-nsn.gov/news_detail_T10_R84.php.

04_Catlin_SpearingSalmon

Catlin, George. Ojibwe Spearing Salmon by Torchlight, 1846-1848, oil on canvas, 19 1⁄2 x 27 1⁄2 in. (49.6 x 69.9 cm), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.575, https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/ojibwe-spearing-salmon-torchlight-4297.

05_Treatyof1837

National Archives Catalog, “Ratified Indian Treaty 223: Chippewa - Wisconsin Territory, July 29, 1837,” https://catalog.archives.gov/id/68144559?objectPage=5.

06_Uttech

Uttech, Tom, Mamakadendagwad, 2015-2016, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase made possible by the American Art Forum, 2017.3, © 2016, Tom Uttech, courtesy Alexandre Gallery, New York, https://edan.si.edu/saam/id/object/2017.3.

07_Dethulstrup, Thure, 1885

Dethulstrup, Thure, Artist. Logging in northern Wisconsin / drawn by T. de Thulstrup, Zimerman & Negri, se. Wisconsin, 1885. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/92501636/.

08_Ford_Sawmill

Baraga County Historical Museum, “1930’s picture of the Ford Sawmill in L’Anse,” http://www.baragacountyhistoricalmuseum.com/photohistory/picture_ford_sawmill_1930s_2.JPG/.

09_Copper_Mining

Baraga County Historical Museum, “1881 detailed aerial drawing of the Village of L’Anse,” http://www.baragacountyhistoricalmuseum.com/photohistory/picture_lanse_1880s_drawing.JPG.

10_Detroit Publishing Co., 1880

Detroit Publishing Co., Publisher. Mills from railroad bridge, Eau Claire, Wis. United States Eau Claire Wisconsin, None. [Between 1880 and 1899] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2016799263/.

11_Stone_Quarry

Baraga County Historical Museum, “1900's picture of an old stone quarry located just north of L’Anse,” http://www.baragacountyhistoricalmuseum.com/photohistory/picture_lanse_1900s_stone_quarry.jpg.