V.

The Necrocene: A Species Perspective

Sam Klein

Alex Nobert

Martin Roland

Angelica Johnson

Preface: The Necrocene

“The death wish of the deep ecologists and the death drive of capital lies in the same misanthropic fantasy of a world emptied of ourselves—the former in a masochistic longing to erase our sins, the latter in the hope to become pure abstract value unmoored from material entropy and death.” –Justin McBrien, “Accumulating Extinction,” 135.

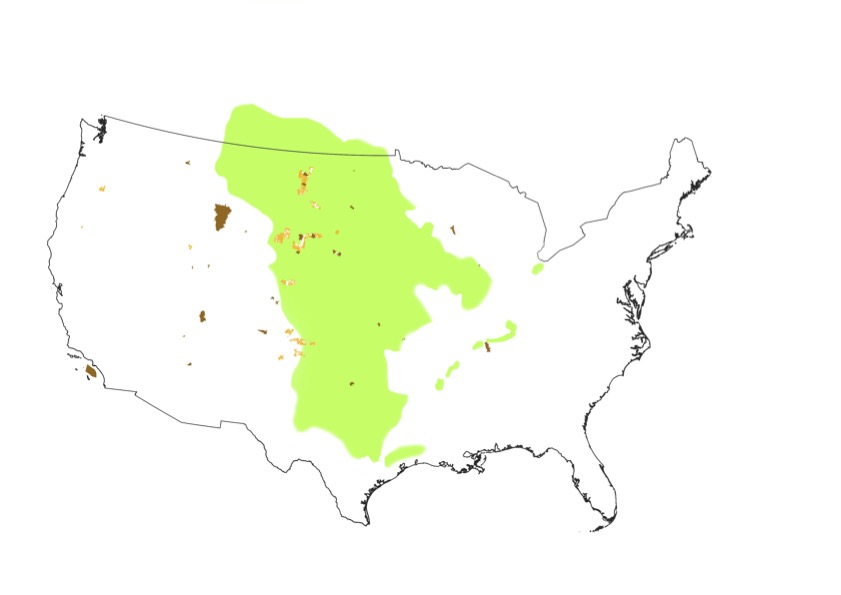

The Necrocene is characterized by habitat and biodiversity loss and emphasizes humanity’s destructive role in this process. While it can be tempting to fall upon a nihilistic or catastrophic view of the future given this framework, the Necrocene is instead meant to capture the insidious forces that dominate the mundanity of our modern lifestyles. Ultimately, catastrophism is an unproductive reaction to the crises of today because it obscures the slow, tragic, and frankly boring nature of these crises.

While our

project does touch on some of these more reactive impulses, it is meant to

explore how the violence of this era is embedded in the mundane ways in

which we restructure and control land. To accomplish this, we focus on the

interconnected story of bison populations and prairie land as a way to

visualize this narrative.

![]()

Part 1: Bison and the Prairie in their Natural State

Upon entering the prairie in its natural state you see a landscape blossoming with bright sounds and colors, with characters enormous and minute, all of which cultivating the prairie ecosystem. Grasses are growing in all places at various heights, creating their own mountainous scenery, building depths with shades of green, yellow, and even tinges of blue-silver like that of the Little Bluestem. Purple hues and specks of white dance across and between the grasses—wildflowers blooming, enticing pollinators like the Iowa Skipper Butterfly. You can hear birds dancing in the sky above and between the grasses alongside the wildflowers, but then there’s a shift in the atmosphere that means something is approaching. Every move of the creature creates a sound of its weight, proclaiming its majestic size with deep vibrating roars, heavy grunts, and sighing snorts. The creature reveals itself through the large hump on its shoulders with long brown shaggy hair draping over its head leading to a mighty set of horns black and crescent curved. It’s the bison, a creature essential to the life surrounding it on the prairie.

Bison roam in the prairie grasslands, tracks making impressions into the prairie land including its soils, wildflowers, and grasses. In every step of its life, the bison co-evolves with the prairie. The prairie breathes with the bison. As bison graze upon the prairie grasses in patches, digging and feeding in different areas, grasses of different heights are left behind. These spaces create nesting areas for birds and opportunity for more prairie wildflowers and other plant species to grow, benefiting insect species, especially pollinators, increasing prairie biodiversity and creating sound vegetation structures (Boyce et al., Martin). While roaming the grasslands, the bison will at times wallow, laying down on the soil then rolling around to cover themselves in dirt and mud to create a protective barrier on their skin from insects, while also shedding old fur and sheltering themselves from the heat (Martin, Ratajczak). This action creates deep impressions in the ground, compacting the soil and providing a unique environment for medicinal and pioneer plants like the wild strawberry to grow (Carroll). The wallows also engineer new water systems in the prairie, creating a space large enough to collect rainwater and even create ponds for amphibians (Mehl) . After roaming, bison naturally enrich the soils of the landscape with nitrogen rich urine and excrement, contributing to its microbial community and attracting more insect species to the prairie like the dung beetles and flies which provide food to prairie species like birds, bats, and box-turtles (U.S. National Park Service). In enriching the soil through increased biodiversity, bison prevent the desertification of the prairie. Because bison interactions within the prairie ecosystem sustain so much of its life, restoration efforts are working to maintain the presence of bison on prairie land in order to bring it back to life once again (Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie).

This flourishing ecosystem, so reliant on the relationship between bison and prairie grasses, resulted in rich soil that only furthered the success of the prairie. Unfortunately, it was also an enticement for the demise of the prairie ecosystem. The fertile soil drew large-scale agricultural development to the prairie land and in this settlement—driven by colonial ideologies of westward expansion—the prairie was forever altered. The world of evergrowing life had entered the twilight of the Necrocene.

Part 2: Westward Expansion: Explicit Violence Against Nature

Alongside the prairie and bison lived Native Americans. Bison provided many services for plains tribes: their meat was used as food, hides used for shelter, and bones used for tools and jewelry (“Bison Hunting”). The Native Americans understood the importance of sustainable hunting practices, and flourished alongside bison as members of the natural prairie ecosystem for centuries. Unfortunately, the peaceful coexistence between the prairie, bison, and Native Americans was not to last. With President Thomas Jefferson completing the Louisiana purchase in 1803 and settlers beginning to stream westward, the land was about to be altered permanently. Bison were hunted on a massive unsustainable scale, in the name of providing meat and hides to the incoming denizens of the West. A 1869 firsthand account from a settler shows the extent of the slaughter: “All over the plains, lying in disgusting masses of putrefaction along valleys and hills, are strewn immense carcasses of wantonly slain buffalo. They line the Kansas Pacific Railroad for two hundred miles” (Webb: 312). By the 1890s, bison were essentially extinct; they had gone from tens of millions strong to only a few thousand.

This wanton, almost wasteful destruction of a keystone species points to a darker ulterior motive: subjugation of Native American populations. “Euroamericans, guided by an ideology of racial and economic conquest, hunted bison in order to destroy the Indians’ primary resource and force them to submit to the reservation system” (Isenberg). This motivation to control land and groups by exploiting their interdependence can relate back to theories on the Necrocene. Greed was the main factor driving Westward Expansion, and capitalism was the tool that settlers brought with them to achieve their goals. The wild prairie was redefined as “settled” and transformed into farmland, townland, and monoculture pastures for domesticated animals. Historical testimony from a hunter called Frank Meyer succinctly summarizes the mass species change of the late 19th century: “the buffalo didn't fit in so well with the white man's encroaching civilization. So he had to go” (Isenberg).

However, this dark narrative of bison slaughter is not the full story. Many additional factors that were also responsible for the near extinction of bison in the 19th century. Recent historical studies have shown how “[an] environmental perspective offers a detailed and nuanced analysis of the bison within the Great Plains, including the natural factors that limited its population such as predation, disease, and drought” (Williams: 32). These natural factors–specifically an extreme drought in the 1850s and cow diseases brought with western settlers–played a large role in weakening bison populations alongside mass hunting. We can best understand the loss of bison as “an example of how loss of range management can trigger a cascade of environmental damage spiraling toward extinctions” (Stoneberg Holt). Human hunting was undeniably the root cause driving bison extinction; however, more natural harbingers of death like drought and disease also played a large role in shaping the historical narrative.

Ultimately, the westward expansion at the end of the 19th century can be seen as a large step into the Necrocene epoch. Hunting, alongside natural factors like disease and drought, brought about the death of countless bison; this loss had harmful ripple effects throughout the prairie ecosystem. The purpose of this destruction was fundamentally to control land, and the previously wild expanses of prairie would be continuously reshaped for human use over the next several centuries.

Part 3: Mass Industry and Habitat Loss: Shift to Implicit Violence

While bison hunting campaigns largely died with the end of the 19th century, the ways in which the continent had been restructured as both an instigator and result of that effort have continued to threaten bison populations. With just twenty-three North American bison left sequestered in Yellowstone in 1900, the American campaign to control the West had gone into effect (Ketcham). While the perception of the American Bison has shifted in the last century and conservation efforts have allowed populations to grow rapidly (the Yellowstone bison population reached 5,000 in the early 20th century), the land in which they may be permitted to exist has largely been destroyed. Policies like the Homestead Act that encouraged struggling easterners to move west and start anew slowly transitioned the land from a sprawling wilderness to fragmented private property. Later, the railroads that stretched from coast to coast became the network of highways that dominate the American landscape today, creating habitat fragmentation that posed major challenges to any migrating or long-range species, including bison (Herkert). The bison populations that have begun to grow and thrive must thus navigate this changed territory.

This tension between bison repopulation efforts that attempt to celebrate their success and the organization of land that hampers it can be seen clearly in the story of the Yellowstone bison population. Over the 20th century the population grew rapidly due to the high reproductive rates and general adaptive success of bison in the area. However, almost since the beginning of the population’s reestablishment the park has experienced tensions with neighboring states as bison wander into public and private lands reserved for other uses. This tension has resulted in fluctuating culling efforts that attempt to maintain the population at a level that can be sustained within the Yellowstone territory (“History of Bison Management in Yellowstone”). In 1995, the state of Montana sued Yellowstone for allowing bison to enter private lands, resulting in the Interagency Bison Management Plan which, among more optimistic plans, required the slaughter of over 1,000 bison (Greater Yellowstone Coalition v. Babbitt).

This lawsuit speaks to the way in which the violent campaigns of the 19th century have become embedded in the very organization of American lands and the systems in which we control them. Even the most optimistic and expansive conservation efforts are limited by the fact that the North American continent is no longer characterized by integrated biomes but rather a collection of fragmented properties. This reconfiguration of the natural landscape becomes an obscured force that remains just as fatal as the hunting campaigns without the clear visual cue of destruction.

Part 4: The Threat of the Necrocene and an Ideal Possible Future

The Necrocene is a foreboding reframing of our current era of significant anthropogenic change on the planet, focusing on the decline of ecosystems and the loss of biodiversity. This term, as we’ve examined in our species perspective narratives, not only represents the death of individual species like the bison but also represents the larger destruction of complex ecological networks and the degradation of the natural environment. The mass extinctions, habitat loss, and climatic changes are grim hallmarks of this epoch, highlighting the irreversible damage humanity has brought to the planet.

In this bleak landscape, the threat of the Necrocene looms large, casting a shadow over the future of countless species, including our own. It is a warning of what may come if current trends continue as they are—a world where the once celebrated biodiversity of the planet is slowly extinguished by the violence; explicit and implicit, spread by human development.

But proponents of this framework agree that only considering this outcome will provide no value to humanity as we try to redirect the current trajectory. We can still imagine a seed of hope where this narrative changes its course, and a more ideal world is realized.

For the bison and the prairie, this kind of world is achievable through various means. Large-scale conservation projects can protect and restore prairie ecosystems. Rewilding efforts, like those undertaken by the American Prairie Reserve and similar organizations, work to reconnect fragmented habitats and reintroduce native species, including bison, to their ancestral lands. These initiatives not only benefit the wildlife but also help sequester carbon, combat climate change, and restore natural water cycles. Transitioning to sustainable agricultural methods that mimic natural processes can reduce the impact on the prairies. Techniques like rotational grazing, polyculture crops, and permaculture design can rejuvenate the soil and create habitats for native species while still providing for human needs. Allowing bison to roam more freely on private land would increase the population size and have ecosystem wide benefits. It is easy to lose sight of optimism under the dark framing of the Necrocene; however, it is essential that we take a positive approach to the possible futures of species like the bison. We can and must reframe the ongoing story of our environment, starting by learning what we can from individual species–like our friends the bison.

Bibliography

“Bison Hunting.” Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, June 14, 2018. https://indigenouspeoplesatlasofcanada.ca/article/bison-hunting/.

Boyce AJ, Shamon H and McShea WJ (2022) “Bison Reintroduction to Mixed-Grass Prairie Is Associated With Increases in Bird Diversity and Cervid Occupancy in Riparian Areas.” Front. Ecol. Evol. 10:821822. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2022.821822.

Carroll, Allyson. “Wallowing: More than Scratching an Itch for Plains Bison.” NCC: Land Lines, 6 Nov. 2021, www.natureconservancy.ca/en/blog/archive/wallowing-more-than.html.

Greater Yellowstone Coalition v. Babbitt (United States District Court, D. Montana, Helena Division December 19, 1996).

Herkert, James R. “The Effects of Habitat Fragmentation on Midwestern Grassland Bird Communities.”Ecological Applications 4, no. 3 (1994): 461–71. https://doi.org/10.2307/1941950.

“History of Bison Management in Yellowstone.” National Park Service. Accessed December 7, 2023. https://www.nps.gov/articles/bison-history-yellowstone.htm.

Isenberg, Andrew. “Social and Environmental Causes and Consequences of the Destruction of the Bison.” Revue Française d’études Américaines, no. 70 (1996): 15–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20874341.

Ketcham, Christopher. “The Government Won’t Let Me Watch Them Kill Bison, so I’m Suing.” VICE, May 21, 2015. https://www.vice.com/en/article/xd7x9k/witness-to-a-massacre-0000652-v22n5.

Martin, Ross. “Where Bison Roam, Prairies Thrive.” Yale Environment Review, 30 Jan. 2023, https://environment-review.yale.edu/where-bison-roam-prairies-thrive.

Mehl, Heidi (2018). "Bison as Engineers of the Prairie Waterscape," Symphony in the Flint Hills Field Journal. https://newprairiepress.org/sfh/2018/nature/5.

“Midewin National Tallgrass Prairie - Resource Management.” Forest Service National Website, www.fs.usda.gov/detail/midewin/landmanagement/resourcemanagement/?cid=FSEPRD533279.

Ratajczak, Zak et al. “Reintroducing bison results in long-running and resilient increases in grassland diversity.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America vol. 119,36 (2022): e2210433119. doi:10.1073/pnas.2210433119.

“Rewilding.” American Prairie, February 18, 2023. https://americanprairie.org/rewilding/.

Stoneberg Holt, Sierra Dawn. “Reinterpreting the 1882 Bison Population Collapse.” Rangelands

40, no. 4 (2018): 106–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rala.2018.05.004.

U.S. National Park Service. “BISON BELLOWS: A Healthy Prairie Relies on Bison Poop (U.S. National Park Service).” National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1 Nov. 2021, www.nps.gov/articles/bison-bellows-10-6-16.htm?utm_source=article&utm_medium=website&utm_campaign=experience_more&utm_content=small.

Webb, William Edward. Buffalo Land: An Authentic Account of the Discoveries, Adventures, and

Mishaps of a Scientific and Sporting party in the Wild West. Project Gutenberg, n.d. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/39674/39674-h/39674-h.htm.

Williams, Roy. “ The Collapse of the Bison: Resolving the Debate,” 2023. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1156&context=history_theses.